Bringing the Forest to Brooklyn: An Interview with Ivy Hickam

Portrait of Ivy Hickam in her Brooklyn studio, courtesy of the artist.

In this studio-to-studio conversation, Brooklyn-based landscape painter Ivy Hickam reflects on her artistic journey, from childhood in Colorado to developing a practice rooted in emotional landscapes and painterly exploration. Ivy’s work balances spontaneity and structure, blending memory, plein air studies, and studio improvisation to capture the spirit of nature in both subtle and monumental ways. In our interview, she opens up about how monotype became a breakthrough process, why she returns to the forest again and again, and how she strives to keep emotion at the forefront of her work.“Connection to nature is so important and it’s something we are losing. So, I make work about it.”

Luis: Thank you for taking the time to do this interview with me, I really appreciate it. To start, can you talk about your background, how did you end up in NYC as a working artist?

Ivy: Thank you for your interest in my work. I grew up south of Denver, moved to NY the summer after I graduated undergrad in early 2005? I had gone to school in upstate NY and a few of my friends were moving to the city for fashion jobs. I had an illustration degree. I had dreams of children’s books, and I thought I’d be here a few years and just see. I went to the New York Academy of Art in 2011. I wanted to officially study painting and the figure and what I developed after that time was my own studio practice. Still in Brooklyn 20 years after arriving here, I guess I’m a New Yorker at this point. And still an artist.

Left: En Plein air studies from a recent winter residency in west Ireland, oil on paper, hanging in Hickam’s studio wall. Right: 70” x 50'“ oil painting during Greenpoint Open Studios, May 2025

Luis: Your subject matter is the landscape and as a city dweller I wonder how you arrived at it? Has it always been of interest to you?

Ivy: You know I’ve thought about this because sometimes I miss the figure. It kind of happened organically. I don’t like painting the figure from photos. In a way that’s really what led me to landscape. I think I started the landscapes when I started to make monotypes. I also started to plein air paint, but it took a while to have a practice and a set up I liked. Then, I needed to figure out a way to work in my studio that I liked. Without a press, without from life. I think I’m getting there. Also, trees, nature, all of that is in me from growing up as a kid in Colorado. Connection to nature is so important and it’s something we are losing. So, I make work about it.

“Monotypes are the cure for painter’s block”

Luis: I can definitely relate to the challenge of not having a press, but regardless, monotype has become very important to my practice over the years. It was out of pure chance really, but it stuck with me to the point of obsession. How did you start making these one of a kind prints? Does monotype inform your paintings or the other way around?

Ivy: I think they inform each other. I call monotypes the cure for painter’s block. I’d love to see more of yours. I made a lot of them right out of grad school, landscapes. At the time I was thinking about what landscapes were a part of my personal history. Which ones could tell the story of a place. I’ve been in the studio and painting outdoors more these past few years. I think I’m trying to make my studio paintings as free as the monotypes and the plein air paintings. But I made my first monotype in years the other week. It was fun. I missed it. How did your obsession with monotype start? And wouldn’t it be fun to have press on hand? Though I wonder if we would ever face the canvas again.

Luis: My obsession with monotype began in 2014 at the Salmagundi Club. I went to one of their monthly monotype parties and I was hooked with the process. I had done monotypes in my printmaking class as an undergrad student at the Hartford Art School, but the process was additive. We painted with etching ink and oils directly on linoleum blocks that were covered with some sort of waxy paper, and we ran it through a press designed for block printing. At the time I was working on large abstract paintings and I was trying to do something similar via the prints. It was an ok experience. At Salmagundi they work with copper plates in a reductive style, and for some reason the mix of the etching ink, the plate, the smell, the feel, and the process all clicked for me. I have been going to the monthly parties ever since. It’s the only way that I can get work done now since I don’t have a press in the studio. I would love to show you some of my monotypes sometime, maybe even have a day together at a print shop and see what we make while discussing life and art. Although monotype and its process technically do fall under the discipline of printmaking, I have come across comments from printmakers that monotype is not real printmaking. How would you respond if you were to come across this sort of comment?

Ivy: I would say I get it. Because I am not a printmaker. I am a painter. I would call it the painter’s print. But I would call it a print. I love that I must work fast in one sitting, on a slippery surface, with different materials and I don’t know what the final output will be till I run it through a big heavy press. I like the lack of control. I got to the point that I was more in control of it, I made so many, but now that I haven’t the excitement of them may be back. It’s good to make things you can’t fully control. It’s fun and you learn from them. You also make beautiful etchings so as an actual printmaker do you feel like your monotypes are more related to your paintings or printmaking processes? Let’s have a print shop day hang for sure. I’d like to pick your brain. I love what you do with your drawings on ghost prints. You get such a quality of depth in those landscapes.

Left: Blue Sky Beetle Kill, 19” x 15”, Monotype, Available through Abend Gallery. RIght: Edge of Suburbia, Monotype, 14” x 11”

Luis: Thank you, I enjoy making the drawings, it’s a meditative process. I am fully there with you when it comes to enjoying the spontaneity of monotype, and how friendly it is to painters. Sometimes it allows me to be more gestural and think more abstractly. It’s an interesting thing to be aware of because I don’t usually think of my paintings that way, although because of monotype I am beginning to loosen up with my paint handling. I have only made two etchings so far. I enrolled in a printmaking class in February of 2020 at the Art Students League to learn the process, but of course covid happened and shut everything down. I never went back to continue my studies, although I want to bad. The etchings I made are closely related to my pen drawings. Those sketchbook drawings came handy when creating my first etching. It allowed me to not think twice about the lines I was putting down. The teacher at that time was impressed because I created a full landscape image as my first etching, as opposed to a single object like most people do when they start. No pun intended, I had just begun to scratch the surface of etching and I have been left with the want of going back to it and exploring further it’s possibilities. I want to see how I can make this age old medium and subject matter more contemporary. One of the challenges I face as a landscape artist is how can I make this sort of imagery attractive or relevant to today's viewer, without losing my own point of view or aesthetic? Is that something you think about when creating your work?

Ivy: Is this a question you ask yourself because of the history of landscape? The burden of that? Has this been done too much already?I think that’s a question I would ask myself more broadly, not even just for landscape, for figurative art, any art really. But yes, the landscape is steeped in history. And I think the answer for me is your own point of view and hand is only yours and that’s what can make the work interesting to a viewer. Or maybe it’s just asking yourself, is this interesting or relevant to me? If so, then hopefully it will resonate with someone else. As far as attractive, I think some of my paintings are pretty, as some art should be. But sometimes I make work that I don’t think will be as attractive to a viewer or something they would want to buy and live with. Such as the paintings I do of the burnt forest. But it’s relevant. And I feel like I need to make it.

Hickam’s most recent large-scale work hangs in her studio.

“I was like, I’ll bring the forest to me—to my studio in Brooklyn.”

Luis: When I visited your studio recently you had just finished a very large painting which was very impressive. What does your process look like when working on something so monumental? Are you working from plein air sketches or imagination? Do memory and imagination play an important role in the studio paintings?

Ivy: Thank you. I’m finally done with that big one. Whew. I usually don’t work quite that large. It started during covid when I was missing the forest. I was like I’ll bring the forest to me, to my studio in Brooklyn. I started with a thumbnail sketch, then I did a big charcoal on throw away paper to plan things (later not really sticking to that fully, I never do). I only had some photos I took from my one camping escape with a friend upstate to work from. I was working from multiple photos, purposely getting lost in where I was in the reference photos and then putting them aside. I was editing and condensing the space for composition. Then I was trying to get in the flow and just paint. I think I succeeded in that, in moments. I learned a lot from the paintings in that series. I have a memory of the feeling I had standing in that forest after being stuck in a cramped apartment and I hope that feeling is present in the work.

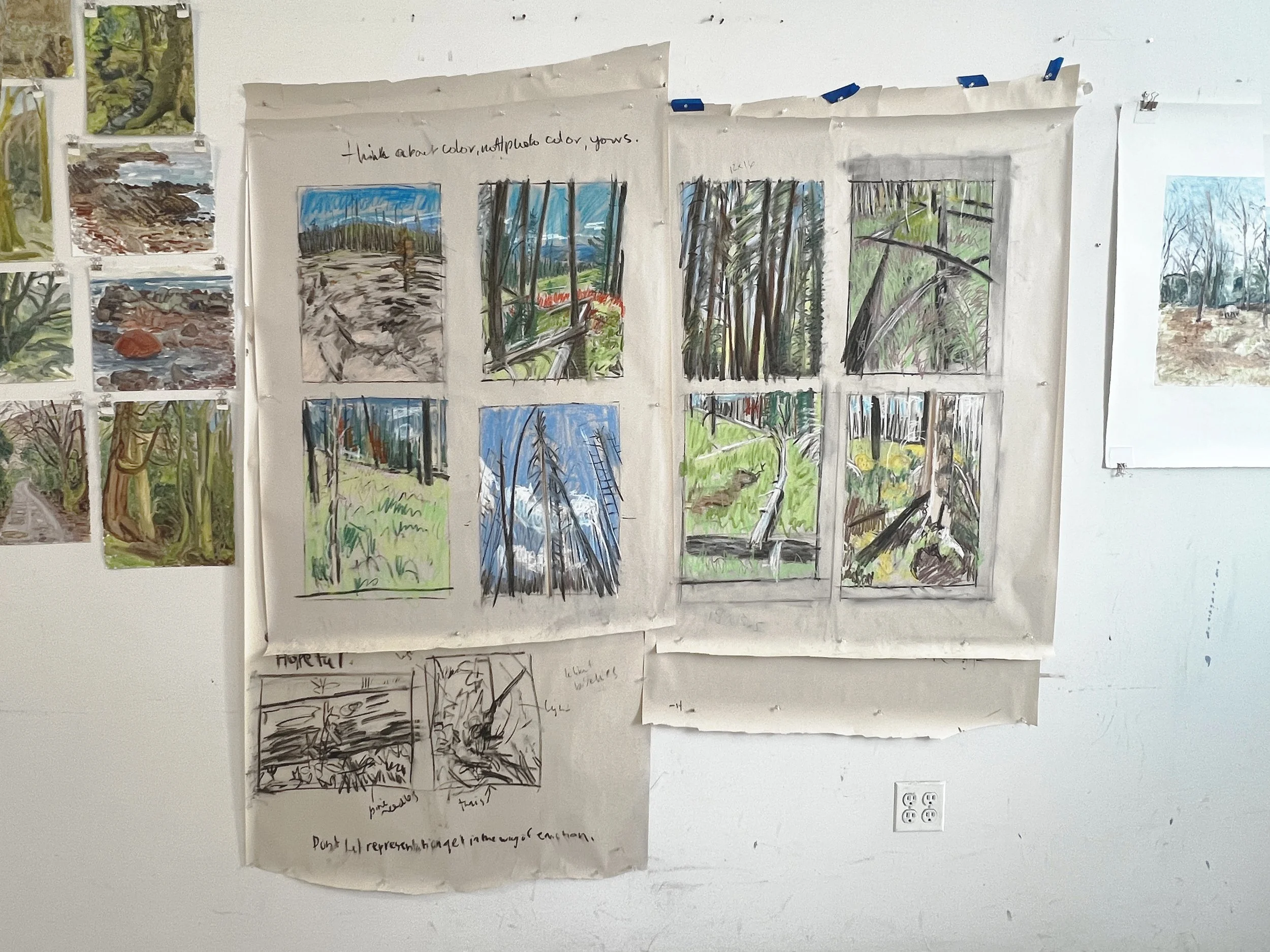

Wall of studies in Hickam’s Brooklyn studio.

“Don’t let representation get in the way of emotion.”

Luis: I saw a note in one of your studies that said "Don't let representation get in the way of emotion," which struck a chord with me. It reminded me of a quote by Cezanne that I love: "A work of art which did not begin in emotion is not art." Can you elaborate more on that? Is emotion and feeling more important than concept?

Ivy: Oh! I love that. I haven't heard that quote from him. I have an old memory of walking in the hot sun, up a hill, from the town he lived to peer into his studio building window. I couldn't really see much. I think it might have been closed for the day. Can't remember. But I do remember the landscape around the house and outside of town looking a lot like his paintings. For me, if I paint the hell out of something and worry too much about representation and accuracy, I can kill what I like about a painting. The movement and the spontaneity of the paint, which I think is how I show emotion. But I think that composition and color theory and all the things that make up a good painting make the emotion too, so it needs to be a balance. So, in other less poetic words I could have written: don't overpaint, don't wipe everything out, trust yourself and don't kill the painting.

“If I paint the hell out of something and worry too much about representation and accuracy, I can kill what I like about a painting.”

Luis: That’s solid advice to any painter, and not very easy to accomplish! Speaking of Cezanne, are there any artists past or present that have influenced your work, and why?

Ivy: More recently for landscapes I was looking at a studio mate’s book on the Tonalists. They made some moody, good paintings. Your work so reminds me of the Tonalists by the way, especially those moonscapes. I love Hockney’s Landscapes. Lois Dodd. The landscape in the foreground of Joan of Arc by Jules Bastien-Lepage at the Met. I was thinking about that while painting the big one I just finished. Also, Joan Mitchell. I wish the Joan of Arc wasn’t newly hung so high. I miss sitting on a bench in front of it, in the hallway, taking it all in. Honestly, that’s the key. To go look at paintings in person. I saw a random watercolor painting of a storm cloud at the Met last week in the drawing and prints gallery. I can’t stop thinking about it.

Jules Bastien-Lepage, Joan of Arc, 1879, oil on canvas, 100 x 110 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Luis: That Joan of Arc painting is wild, I can’t wrap my head around it. It’s not just the technicality but also the emotion in the work. Again we go back to that topic, emotion. But to be honest, as painters we are blessed with a medium that can lend itself to both technicality and emotion. When you hit both of them on the head, together in one piece, then magic like no other has been created. The same can be said about the Tonalists, a school of painting I have admired for many years because of how emotional and moody their works are. Especially Inness! It’s funny you mention Joan Mitchell too because when I was in undergrad I was looking a lot at her work. I was looking at a lot of the Abstract Expressionists period, but her work, more so the later paintings, captured my interest. They were very much inspired by Monet’s Giverny paintings, and Monet has become one of my biggest influence too…it’s funny, landscape and elements of it were there all along while I was learning to handle paint and I never knew it, it is only just now I’m making all these correlations…wow! I can see the influence of Joan Mitchell, I remember looking at the bottom left corner of your big painting and was drawn to its gesture, the boldness of it, and although I didn’t tell you it did remind me of Mitchell’s daring paint handling. Hockney’s paintings are something I never got into, and I wish I could because many people reference him. But you did show me a book containing his drawings, and thanks to you I’m begging to open up to him. Thank you for that.

Ivy: I would have never known you were looking at abstract expressionists in undergrad looking at your current work. Perhaps that’s why you like making monotypes! But yes! Mitchell, Monet, the history of landscape, it’s all connected. She wasn't even on my radar until I saw her work hanging at a New York gallery. Living here has been my greatest education. As for Hockney, it’s the Yorkshire landscapes that got me, they’re so personal. Honestly, I just want to be like Hockney one day. He is not tied to one type of working, always learning. And I used to worry about influence. Question if my work is too much like the artists I'm looking at. Don't we all worry. But Hockney is looking back at the art before him, and he owns it. You have to just own it because we all have our own hand, our own mark anyway.

Luis: I agree with you that as artists it’s such a huge privilege to be in New York because we have so many galleries and museums where we can experience art of the past and present first hand. I know for a fact that I have been influenced by a lot of the work I have seen at the Met, either permanent collection or traveling exhibitions. Currently I have an affinity to French landscape painting, from the Barbizon School through the Impressionists and Post Impressionist. Corot has been my God pretty much. With that said, I don’t try to imitate, but I have been looking at and admiring these guys for so long that it’s hard to shake them off. I do try to make my work my own but their influence can definitely be seen. In the end, like you said, my hand is at play, so is my way of seeing color and how I use it, and so that’s how the work does end up being my own. But at some point I want to break away from it all and create a visual language that’s more my own, something that speaks to current life. That’s what I hope to do soon. How can I create paintings that are very mine but still have a connection to the past without looking like I’m imitating. The goal is there, I just have to keep pushing paint around and hope to arrive at it before I’m old and grey.

So, what is next for you? Are there any new exhibitions or projects you are working on?

Ivy: I’m starting to paint a smaller in scale series from the composition drawings I had up that you saw at my open studios. I’m trying to keep them in the emotion, looser and fast and I’m playing around a bit. Trying new things. As far as exhibitions go, I’m hoping that if I keep making the work that I feel strongly about that’ll come.

Thank you to Ivy Hickam for taking the time to do this interview. I look forward to seeing more of her work in the future. Follow Ivy Hickam on Instagram: @ivyhickam

See more of Ivy Hickam’s work: ivyhickam.com